OUR FAMILY (Hermann's own family history)

M. Max Fechenbach, master butcher and restaurant proprietor, fruit and coal merchant, President of the synagogue, trustee of the congregation and member of the Jewish Council - was all of these and proud of it. He used to say: Too bad that my parents could not have lived to see this. The youngest son of Lazarus and Jetta Fechenbach, he was born on 6th February 1870, in the Jews Alley, Mergentheim. He had registered on police station records with the name "Michael" which his parents greatly regretted at once since he would certainly be called Michael all his life. At that time It was the usual practice to call the simple minded people "Dumb Michael". They tried to have the "Michael" changed to "Max" but it was no longer possible. Nevertheless the second name was added on. Thus my father remained for all time M. Max Fechenbach.

He received a strict orthodox Jewish upbringing, as did all his brothers and sisters, and he remained an orthodox all his life. Max spent his apprenticeship and journeyman years in Hamburg and Hannover. His two years active military service in Ulm on the Danube, and was discharged with the rank of lance-corporal in the reserves.

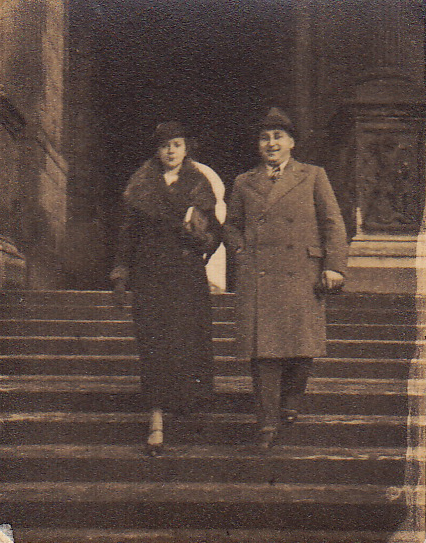

M. Max Fechenbach married Sophie Flegenheimer on 12th February 1895. She had been born in Swabian Hall on 8 th November 1871. He then took over from his father, Lazarus Fechenbach, the butcher's shop and the restaurant/hotel, which were run under strict kashrut regulations. How much extra care were involved In this could only be imagined by someone who has himself experienced the daily routine of carrying on such a business. In addition to this, my parents could never bring themselves to leave important work to the staff. Thus they had to be busy from early morning until late at night.

It was an advantage for the butcher shop that at that time there was an up-to-date slaughterhouse available in Mergentheim, equipped with cold storage facilities. My father had to undertake the purchasing of cattle from the surrounding farms himself. From the cattle dealers who came to our business he would usually find out which farmers selling suitable livestock for slaughter. Grandfather Lazarus also still travelled about the countryside, buying hens and eggs for the business, and so was able to find out where the best cattle were to be found. The farmers found in cattle dealing a refreshing change from the hard agricultural labour of that time, and it was the general custom to deal with Jewish buyers. The animal was rarely weighed; the butcher himself estimated the weight. Furthermore, my father had to make sure that the cow or calf was absolutely healthy. The entire transaction would be concluded when an agreement was reached and confirmed by a handshake. Father often had to bring the animal he had purchased home over a distance of several miles, assisted by an apprentice, and I too had many opportunities to help him out with this.

My mother's cooking abilities were highly prized at the restaurant, so she always had requests from young girls to learn cooking from her. A kitchen helper and a serving maid were also continually available. Everything had to be attended to for the regular daily customers, for travellers, and In the manner for guests who had come for the baths. Although generally these were people who required kosher meals, Christian guests came as well who knew how to appreciate my mother's culinary arts.

The classification of kitchen work was especially supervised, since meat and dairy utensils had to be strictly separated, to the extent that both types could not be washed together. The large restaurant stove contained a baking oven and a water tank and early every morning it was heated with wood and coke. All meat and poultry, even though slaughtered according to regulations, had to be washed and salted for an hour before preparation, so that there was no trace of blood remaining. Likewise the different kinds of liver had to be roasted over the grill before further preparation.

On 23rd November 1895, a son was born and received the fine name of Siegfried. Even though the orthodox Jewish point of view made a closer relationship with the Christian surroundings difficult, they nevertheless made efforts to resemble them along the lines permitted. The name Siegfried from German heroic epics was used so much among the Jews that it was hardly to be heard anymore in Christian circles. The circumcision took place eight days after the birth, and after another three weeks my mother was again able to attend Sabbath services at the synagogue. At the same time an invitation posted in the synagogue courtyard for the "Holegrasch" which took place at 2.00 pm in the Fechenbach restaurant. All the children of the community between the ages of two and twelve had already assembled and were waiting for the teacher, Pappenheimer, who soon appeared and stood near the baby carriage where the newborn infant lay. Then he spoke the age-old blessing of the patriarchs Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, and the crowd of children gathered around repeated each word and shouted at the end, "Holegrasch, what shall this child be called?" The ten to twelve year olds held the baby carriage while the teacher called out the name Siegfried, and then they lifted it into the air three times as they all called out together, "Holegrasch, what shall this child be called, Siegfried, Siegfried, Siegfried". For all the children the best part was the distribution of paper bags, full of delicacies, a whole big wash-basket full, all prepared by my parents. Beaming with joy they all went away, the bigger children and the very small ones with their new-won riches.

Barely one year later, on 11th January 1897, around 11.00 pm, my sister Rosel was born and my father was so delighted with his daughter that he immediately sent a telegraph message to his ln-laws Isidor and Helene Flegenheimer in Swabian Hall with news of the happy event. Even though the messenger came around at 2.00 am and woke grandfather up from a sound sleep, the news was received with great happiness. But when the grandparents were awakened one hour later once again by the telegram messenger, grandfather gave him an especially large tip so as not to see him anymore. Thus was I born and it was a big surprise when Dr. Kalner the physician said, "The twin cavalier Is coming here!" Naturally no one had counted on me but my sister and I were so small that one more made no difference. A well-meaning neighbour who had twins herself and so wanted to see us, told my mother when she saw how tiny we were: "If these two were mine they'd have long been back in the Kingdom of Heaven". As already mentioned, my little sister and I were an extra great care for my parents, who were all the more anxious as nature had been so uneconomical, to keep us alive in spite of our weak condition. Our family doctor gave recommendations without end, and a full-bosomed wet nurse was found In Neuklrchen, who was able to give us poor weaklings her extra milk, to our profit. It goes without saying that my parents now seriously resolved to put an end to the 'Stork' for good. Where would they end up if such double surprises turned up every year!

I had my circumcision according to regulations and together with my little sister we had our "Holegrasch". She was called Rosa, and I received the fine name of Hermann in honour of a rich American uncle, who, if I remember correctly took absolutely no notice of my existence.

My parents really kept their word; we three were enough, for work in the restaurant and the butcher shop kept them busy from early morning until late at night, and they hardly had any time to look after us during the day. A 15 year old peasant girl from Wachbach was given the duty of keeping a watchful eye on us, and 'Marie' did this faithfully for the next few years. She went walking with us every day in the nearby park so we could enjoy the full effect of the wonderfully pure air. In bad weather our children's room was large enough for us to crawl and run, to talk and learn prayers, out of the way of the business activities. In the beginning, Mother pronounced the Hebrew sentences for grace after meals and the bed time prayer, and our nurse maid very quickly took the responsibility for us saying our prayers on time.

On weekdays, we children were permitted to wish our parents good morning early In the day and good night in the evening. On Sabbath mornings, however, we were allowed to go into their bedroom and lie in bed with them. This was always a great pleasure for us.

Before the age of three, pencils and chalk already made a very strong impression on me. It gave me an extraordinary satisfaction when I worked with them on slate or paper. I always had to keep looking at all of the pictures we had in the restaurant, the guest rooms and the bedrooms, and they accompanied me throughout my childhood. The two old engravings hung in our children's room -Moses with the Ten Commandments and the Sacrifice of Isaac. In the guest room hung the flight from Sodom and Gomorrha, a reproduction of Rubens' painting, as well as a large family portrait of Kaiser Wilhelm II, and the one-time extremely popular prints "The Warrior's Farewell" and "The Warrior's Return" hung in frames over the guest beds.

In the restaurant there were large photographs of Kaiser Wilhelm II, of his wife, of King Wilhelm II of Württemberg and his wife. Likewise, a portrait of the Regent Kaiser Friedrich III, who was always held in honour by the Jews, and had ruled for only 90 days, had a place of honour in our restaurant. These pictures testified to my father's patriotic attitude; he even wore a proudly groomed Kaiser Wilhelm moustache. Naturally this attitude was transmitted to me, and I was convinced that Kaiser Wilhelm, who I was constantly trying to draw, came directly from God. The single colour reproduction in our house hung in my parents' bedroom over the headboard. This was of two angels' heads, a detail from Raphael's Sistlne Madonna, which looked down on me protectively.

On Sabbath morning Siegfried was allowed for the first time to accompany my father to the synagogue. My mother gave him pennants embroidered with his name which were used to tie the Torah scrolls together, and were then used to wrap around them. Rosel and I remained alone at home, and since no guests were expected at that time, we used the opportunity to run around and play in the rooms.

Suddenly the restaurant door opened, and our friend and regular customer, Salomon Strauss, entered. We ran into his arms happily. Soon Rosel on the right, and myself on the left were sitting on his knees and he was playing "hop, hop rider" with us. When he had had enough of us, Rosel and I received a penny from him and he said, "Go buy yourselves a kingdom". We had no idea of what this money in our hands signified, but this much was clear to us that things could be bought with it. We were usually around when our nurse maid did the household shopping, and we were always given sweets. What would we get now for our money when we went shopping? Since the Merz'sche pharmacist always gave us the best treats, we decided to go there first. At this time there was hardly anyone to be seen on the streets, and thus we trotted hand in hand to the central market place. We climbed up the stone steps, then I opened the shop door with great difficulty. The shop counter was also too high for me and I could hardly see the proprietor. So we both stood without saying a word, held our wealth out in our hands and awaited, full of anticipation for what would happen next. The proprietor had to consider how to deal with this type of customer. Finally he handed us a stick of licorice and some carob. Naturally this did not correspond to our expectations, but we nonetheless returned home contented. Meanwhile our parents had been informed how hand in hand we had taken care of our purchase, but Father showed little understanding of this. The orthodox Sabbath laws must be observed in our family under all circumstances. What sort of reputation would a kosher restaurant acquire if the owners permitted their children to go shopping on Sabbath. Furthermore my parents could not conceive of where we had got hold of the money, for even touching money on Sabbath was forbidden, and then to go and buy something with it - this was considered an unpardonable sin. Of course we had no idea what we had done and we had to be taught.

As on all holidays after the service and before the noontime meal, we were taken to see our grandparents in Mühlwehrstrasse, so that they could lay their hands on our heads in blessing. But this time, Father was waiting for us, and his hands landed painfully on our backsides, while he explained that we had sinned. This method of education had an enduring effect, but a certain fear of my father's "quickness of hand" remained in me forever.

At that time Mergentheim was an ideal town for children - they could play in the streets undisturbed. The farmers' wagons left early in the morning for the fields and only returned at evening, loaded with hay and straw. There were very few horse-drawn coaches. Marie still took us on excursions to the park and told us old peasant stories all the while.

Now came the time for me also to visit the synagogue for the first time on Sabbath to offer the pennants Mother had embroidered with my name. For weeks in advance I was excited about this great experience, most especially because I was measured for my first men's clothing and at last was able to wear proper boy's trousers. After all these preparations the long awaited Sabbath arrived. I was most seriously instructed not to speak in the synagogue, and to remain quiet at all times. The totally new impression that the large synagogue hall made upon me, the gallery with the women and especially the many men, wrapped in black and white striped prayer shawls was in itself sufficient to render me speechless with astonishment anyway. For a short time I sank down among the high pews that completely blocked my view, and then Father picked me up in his arms and carried me to the pulpit. Here I handed over my pennants and could observe how they were wrapped around the Torah scrolls. Then Father carried me outside to where our nurse maid was already waiting to take me home.

Whereas up to now I had been under supervision and at the most could play in our courtyard, now I ventured into the streets where the show window of the toy shop especially had an irresistible attraction for me. I already knew that Father and Mother were not in a position to buy us playthings, so Just for that reason, everything on display in the show window seemed like fairyland: dolls in all sizes, whole armies of soldiers, guns, boxes of bricks and lead soldiers. Whatever toys we children had came from Aunt Therese from Karlsruhe and Aunt Auguste from Augsburg. At our grandparents' house we had a rocking-horse with real horse-hair and a leather saddle, which always received thorough use when I visited. A sabre that Father made himself and a newspaper helmet were completely sufficient to satisfy my military requirements.

Every horse I saw increased my enthusiasm for this animal, and I would dream of lying in the stable with them and being warmed by their powerful bodies. I could not understand why they had to pull such heavy loads and I wished that all wagons could be pulled by steam engines. Nevertheless I was terribly afraid of them and was entirely satisfied to marvel at them from a distance. When the soldiers returned from their drills and marched through MUhlwehrstrasse, it was not the music alone that made my heart beat stronger with joy, but the captain on horseback. The Royal Wtlrttemberg 122nd Infantry Regiment had its barracks in the castle, and one could watch them being drilled every day by their officers. Playing at soldiers was therefore a favourite pastime for even the youngest children. However I was not overly thrilled by having to obey others' commands.

Nearly every day Rosel and I visited our grandparents, who lived on the first floor of Bessler's saddlery in MUhlwehrstrasse. Since the Bessler family's children were our age, it was understood that we would become friends and play with each other. When little Anton's mother sent him to the neighbouring butcher to pay a bill, I could accompany him. The butcher gave us both a little bit of sausage that we devoured with gusto immediately. Frau Bessler told me later that I should not have eaten this gift, since it was not kosher, and she warned me never to tell anyone about it. Since I had not forgotten my tale of woe with money on Sabbath, I was grateful for this warning and took great care not to let any hint of this incident become known.

Whenever we met Grandfather Fechenbach on the street, he had nuts, apples or pears for us and he would pull them out of his pockets. If we met him on a Friday then he would tell us that Grandmother had baked a three-layered cake and that we should go see her at once. Naturally we did not wait to be asked twice. In the winter when we entered our grandparents' house with cold hands and cheeks, roasted apples were there waiting for us. First Grandfather had to warm Rosel and me up which we did by first laying our his handkerchief on the oven and then holding it on our red faces.

We quickly found new playmates in MUhlwehrstrasse. Carola and Hedwig, Hermann Hirsch's daughters, the Hartheimer children and Simon Strauss' children, Alvin, Max, Hedwig and Siegfried, and they would all play games of hide-and-seek with us.

Food always tasted excellent and this was noticed too, for all my acquaintances called me Fatty. When Mother ladled out soup for me, I could say "No so much oth Its oo", which naturally meant, "Not so much broth, bits too". This remark escaped from me especially when there was noodle soup but if asked what was my favourite food - the answer was "potaties".

There was a time when the least thing would cause me to break out crying so that even Mother grew irritated. My parents had a good measure of worries. I only wish to mention here how much effort it cost them to save money all the time to buy cattle from the farmers. Understandably, they had little patience with us. Father's quickness of hand and his words as he punished me, "Now at least you have something to cry about" cured me. Whereas we twins were taken care of in our early years almost entirely by our nurse maid, Siegfried had the good fortune to make friends with a young neighbour girl who greatly influenced his interest In reading. Nearly every day he would visit Schlossberger's house, where Dora would read with pleasure from many books of fairy tales and found him an appreciative audience.

The attempt to send us both to the Catholic children's school was a quick failure. As long as I sat in the schoolroom and also got my fabric to pick out, I still found it somewhat endurable, although I would have much preferred to be drawing. But the recess period, when the children would run around shouting and throw sand at each other, was most unpleasant for Rosel and me. A Christmas presentation that I saw there made a very strong impression on me for I had never seen anything like it. A lovely Madonna was surrounded by little angels, all In white, with little silver and gold wings. I didn't understand the words that each child recited, rather the magnificent display of colours altogether enchanted me. Nevertheless these children were far too wild for us, and I did not like it at all that the bigger schoolchildren mocked the smaller ones and called them "Coffee dribblers".

I had only a few playmates, for meetings with other children were always very brief, and I preferred to keep myself occupied alone. In our children's room the three chairs lined up one behind another provided me with my railroad train to board and climb down from. Aunt Auguste's stone building blocks could keep me busy for a long time, but there were always far to few blocks, since I was not content with a mere facade and there were never enough blocks for a house with a room, doors and windows.

It was an incomprehensible event for me when Grandfather Lazarus Fechenbach died on 9th July 1903 at the age of 84. The many preparations for the funeral, the visits from friends, acquaintances, aunts and uncles, had me in a whirl, and I could hardly feel the great loss. We children received gifts from every quarter and the aunts took care that we were not forgotten. Just before the funeral procession started, Father decided that I should attend the funeral. So that I would not get hungry I was given a lovely piece of sweet bread which I hastily put in my trouser pocket. I was allowed to walk near Father in the procession and was lost amidst all the large black-clad men In high top hats. A crowd lined Mühlwehrstrasse on both sides, people lined up several deep to pay their last respects to the departed. I walked along as though in a dream and suddenly felt the piece of bread in my pocket, pulled it out and began to eat without thinking of doing anything wrong. When Father saw me eating I got my ears boxed, so that the piece of bread flew out of my hand and vanished. Only then my real grief began, for I had not expected such punishment. Nevertheless it was clear to me without further explanation what I had done. The funeral procession moved slowly through the town and stopped before the Tauber Bridge to speak a last farewell to the departed.

Here spoke Rabbi Dr. Sánger told of the irreplaceable loss suffered by the faithful wife of the deceased, by his sons, daughters and grandchildren. But not only these, also the Hebrew Community mourned one of its most helpful, industrious and pious members, an extraordinary man who bequeathed to Mergentheim and the surrounding area not only a good name, but also many friends. One had only to look around to see how many citizens of Mergentheim were paying their last respects. Lost among these many men, I stood hemmed in, a whole forest of men's legs surrounding me. My view was completely blocked, the heat was unbearable, and I only longed for some air. With my last strength I tried to get away and sat down on a pile of stones, weary and dejected far away from the gathering. When Father saw me sitting there so miserably he sent me back home. The friends, relations, teachers and rabbis accompanied the deceased in carriages to Unterbalbach, to offer the last prayers there. After the funeral I found Father and all the aunts and uncles sitting on sacks of straw nearly on the floor. I could not understand this but hardly thought to ask the meaning, since we were usually only allowed to say something if we were asked by an adult. This was the seven day "shiva" sitting in the first week of morning. In the house of the deceased also a small oil lamp burned for a whole year, and during the time of morning there was no dancing or piano playing on the business premises.

Rosel and I were Introduced into David Frtthlich's house, where Mother Frtthlich presented KlaYchen and Jakob to us - they were our age. The older children Max and Selma, as well as the younger ones, Sophie and Hugo, all joined In our games in the children's room. The Frtthlich family had a new addition nearly every year. Nonetheless Mother Frtthlich knew how to maintain order. The children were not hit, but there were other punishments that worked extraordinarily well: - three days without dessert, confinement to the house, and so on. Often the mere threat of these punishments was sufficient.

In the summer months, especially during holidays, we had to take care of guests who had come for the baths, as well as the regular clientele. Our parents found it a great relief at this time to be able to send us off to SchwMbisch Hall to visit our Flegenheimer grandparents. The train ride was a grand new experience, and as I pressed my nose flat against the window I could not understand how meadows, fields and woods appeared to be turning in circles and the telegraph wires would rise and fall. So the farmyards, cows, calves, horses and hens moved by us and sometimes hares and deer would also spring up in alarm. Mother watched closely to make sure that no windows were opened. In Crailsheim she found the train we had to change to for SchwSbisch Hall immediately. The three hour train journey seemed like an eternity to us, since we were so eager to see again all our dear relatives who used to spoil us in every possible way. Grandfather and Aunt Therese met us at the railway station; then we went downhill to the first wooden covered coach bridge, past Solbad to a second bridge, and then finally through a narrow alley to the house where Grandmother was waiting for us on the second floor. The table in the living room was prepared to welcome us, with apple and plum biscuits - one's mouth watered at the sight.

As much as we liked being with our grandparents, we liked staying with Aunt Therese, Mother's sister, even better. First of all we didn't have to go to bed so early there. Best of all I liked to stay with Adolf Flegenheimer, for I thought it was a garden of paradise where we could play hide and seek behind gooseberry bushes and grapevines. All the children in the family also gathered here and in the open garden house we were served the most wonderful bread and butter with chives, and lemonade. At that time Julius Flegenheimer was my best friend. I was not homesick, but when they came to bring us back I enjoyed the trip home and was happy to see my village again.

Siegfried was already attending the first class in primary school and his ABC book greatly Impressed me. Writing letters gave me the same pleasure as drawing did, and so I began to copy these printed characters exactly. We had no picture books, but the illustrated "Week" took place of these, and I was always content when I found my honoured Kaiser appearing In its pages. As often as I could, I tried to draw him as closely as I was able. It was also easy for me to learn nonsense, and I myself was unable to understand how It came about that one day I recited my verses In the kitchen before an audience of the entire staff:

All cats are grey In

dark of night When Papa

kisses Mama He's kissing

his wife.

I had to recite these lines over and over again, and I could not understand the wild success they had.

© 2021 • Site by numodesign.com